Synopsis

A. One of the leading causes of environmental pollution is clothing and textiles — hence, the potential for environmental saving there is fantastic. I’ve written about Patagonia, the Californian company, which has done some remarkable things. Socially concerned businesses should apply the following criteria: Is it highly impactful yet? The answer is usually, no, says Geoffrey G. Jones.

Geoffrey G. Jones is the Isidor Straus Professor of Business History at Harvard Business School. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das, he discusses the evolution of socially responsible companies:

Q. In your book ‘Deeply Responsible Business’, what factors shaped values-driven leadership?

A. Each of the business leaders I’ve described faced particular external crises. In an earlier era, some were concerned about colonialism and their nation’s backwardness. Today, some care about inequality or the ecological crisis. Each of these people arrived at their views about responsibility in the face of an external challenge — they saw business as a way to address that.

Q. What is the difference between what you term ‘deep responsibility’ and corporate social responsibility (CSR)?

A. My view about CSR is somewhat cynical in the sense that 95% of the things a company does might not be very good for society but it gives away five percent of its profits for good causes. That will never radically change the world — in contrast, deeply responsible leaders argue that everything they do should make a positive contribution, including the product or service they provide. Secondly, how they operate must be proper, which means treating their employees, other stakeholders and government fairly. Thirdly, they support and sustain communities. This is quite different from giving 5% to good causes — deep responsibility is a holistic view. Such leaders also believe making profits is a means to an end, rather than the end itself. Their values can come from spiritualism, Hinduism, Jainism, a Quaker philosophy, etc. These also stop them from backsliding — as a business grows, there is a tendency for its ethics to diminish and the emphasis on profitmaking to increase. However, having a strong value set helps companies avoid that slippery slope.

Q. Why should businesses care about social purpose? Isn’t that the job of governments, administrators and NGOs?

A. Firstly, business has a license to operate from society — if a company is seen as being exploitative or doing harm, it faces the risk of that being withdrawn. That has happened with firms being nationalised or regulated. Business has a self-interest in being seen as a positive force, rather than the opposite. Secondly, many countries have huge societal problems which governments struggle to address. There is an opportunity as well as an obligation for powerful or affluent organisations to play their part in a resource-constrained world.

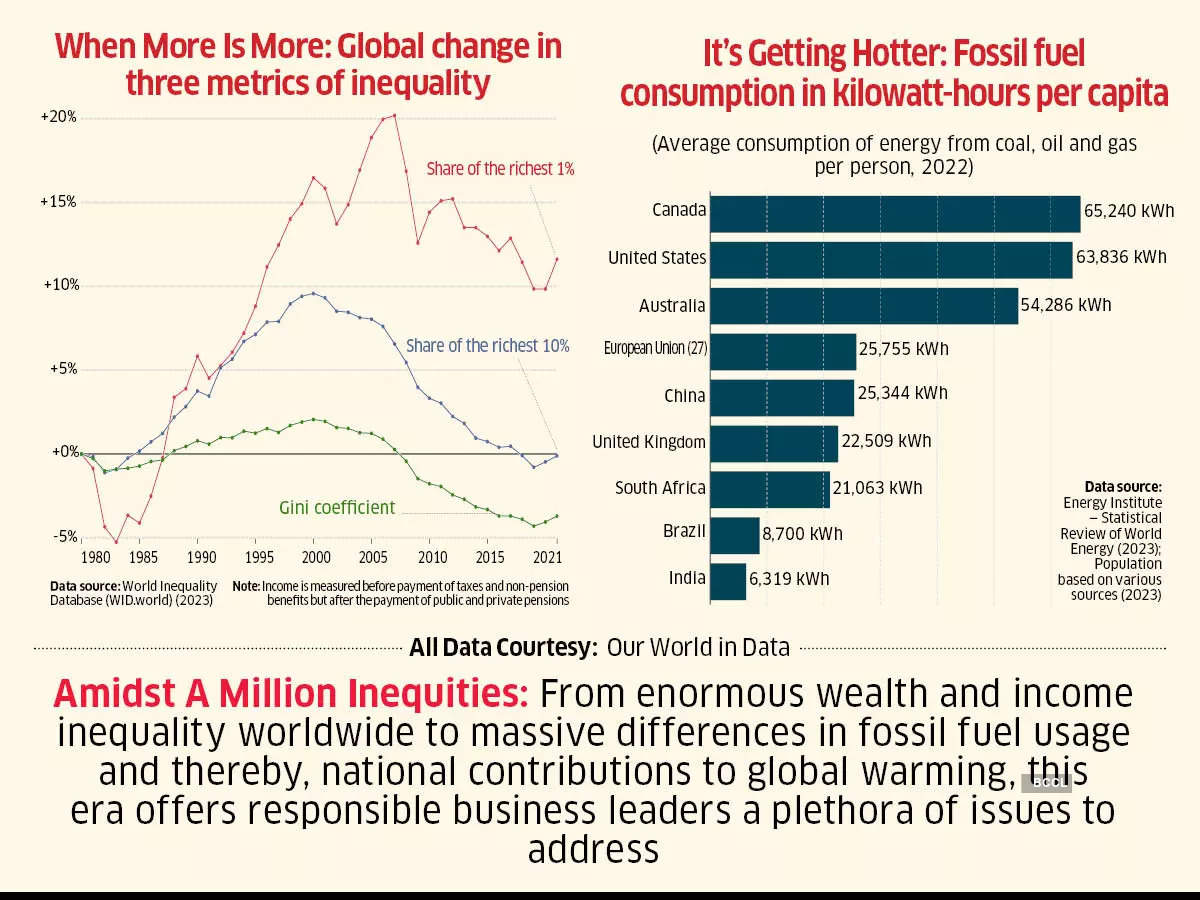

Q. Income inequality is soaring globally — how does this impact enterprise?

A. Such inequality is discrediting capitalism in the eyes of many around the world now. It’s also leading to state intervention, with Xi Jinping in China, for instance, responding to rising inequality by reasserting state control and curbing the power of businesses. You can see parallels in the United States with some Democratic Party policies. This phenomenon poses serious problems of delegitimisation for business which isn’t seen as having a clean hand in situations where chief executives, for instance, grow extremely rich while workers get paid very little. The risk is a hostile reaction from governments or consumers.

Q. Why do you suggest being ‘crazy’ is helpful for companies seeking impact?

A. Here, ‘craziness’ is used in the sense that some people simply don’t accept the norms. They don’t consider these good enough and decide to do something very different. Often, the so-called crazy thing becomes the new norm. Very few people cared about the environment in the past — today, several do. These ‘crazy’ folk are in fact predictors of the future.

Q. You describe how companies and consumers shaped a ‘counterculture’ challenging old-school capitalism in Western economies — how do you see this evolve in emerging markets?

A. To be accurate, that counterculture is not very huge in the West — the willingness to pay extra for sustainability, for instance, is low, except in certain pockets. However, there is a larger market for organic products and such goods because there is more discretionary income.

Yet, we are seeing a generational shift occur now. Younger consumers here are extremely aware of realities like the environmental crisis. They are also a lot less privileged than older generations — in the US, many young people can’t afford to buy a house now as property prices have skyrocketed. So, there is an awareness of social problems along with personal experience that things are not working as they should. That is prompting changes among consumers. It is also sparking new kinds of entrepreneurial startups trying to correct some of these imbalances.

Q. What are some interesting products and services deeply responsible businesses have created?

A. One of the leading causes of environmental pollution is clothing and textiles — hence, the potential for environmental saving there is fantastic. I’ve written about Patagonia, the Californian company, which has done some remarkable things. Socially concerned businesses should apply the following criteria: Is it highly impactful yet? The answer is usually, no. Does it have the potential to be so? Absolutely. In the past, people pioneered wind and solar energy — today, these have become mainstream. Those were deeply responsible leaders. Each generation has such people who seek to address the problems of their age.

Views expressed are personal