Look a bit closer (like his new EP suggests), and you’ll see a surprising depth and complexity to the now-family man and his message—one that preaches self-respect, self-fulfilment and self-realisation—all while having a phenomenal time with his intercontinental legion of fans

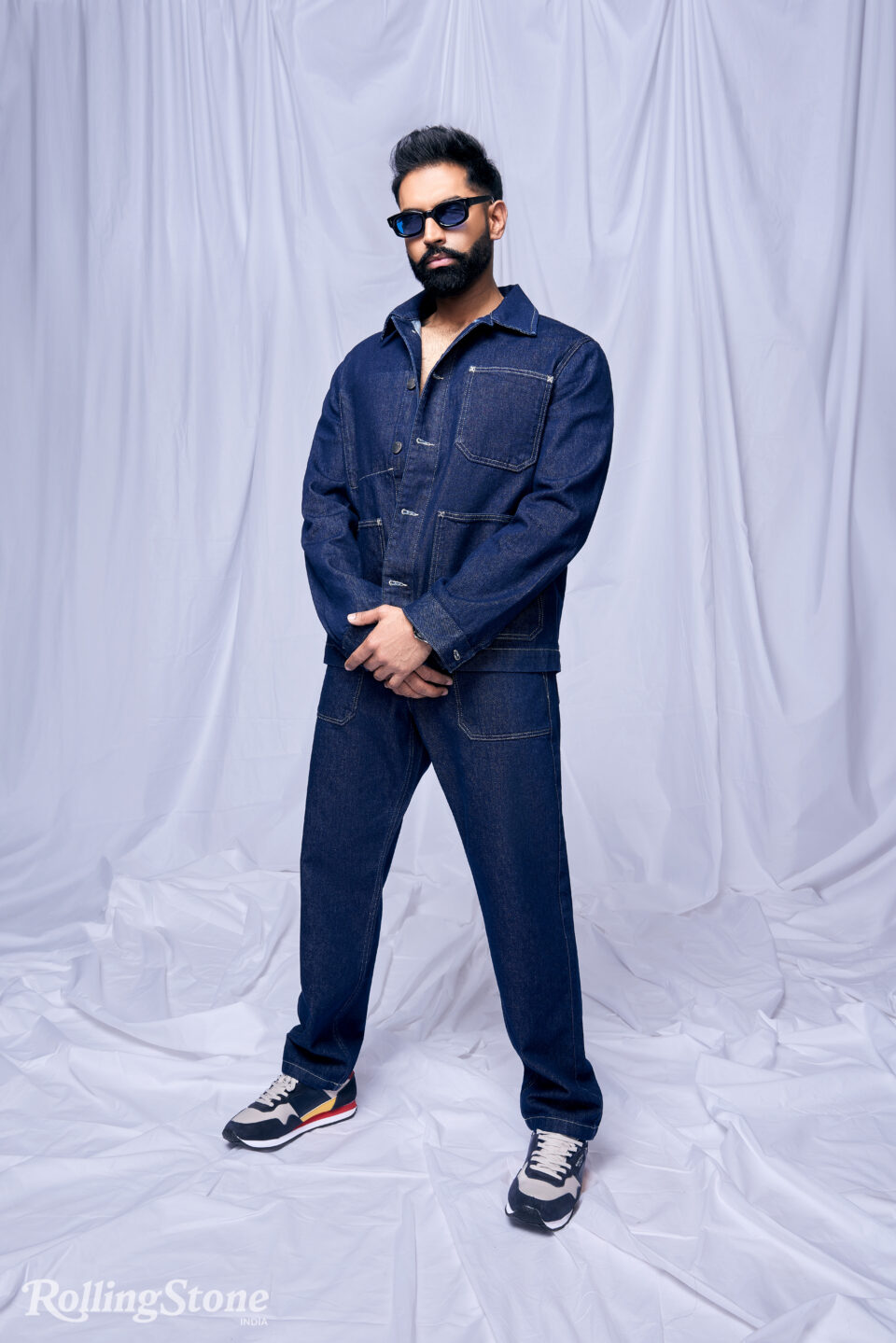

Parmish Verma’s quick quip — one that waved away concerns that he had been shooting non-stop for hours leading up to our interview, really captures the man in a nutshell. The Patiala-born multihyphenate remains spry, active, curious, and deeply collaborative, diving into poses and playing with his wardrobe. One could call his demeanour effortless, though after learning his story, ‘effortless’ really would be a poor choice of words.

Born right at the cusp of Gurdaas Mann’s fame in the nascent 90s, Verma was growing up alongside the burgeoning crucible of vocal delivery, social issues and cultural pride that has since characterised mainstream Punjabi music. Raised in an academic household, the singer-music video director was surrounded by an extensive library in his youth, where his father likely drew inspiration for theatre scripts and a desire to act; an unfulfilled dream that Verma would carry onwards in his early twenties.

Today, at 33, life is significantly different. After leaving behind hotel management and cracking the mid-2000s residence-permit rush in Australia, Verma set his sights on stardom, with music video shoots in Mohali and Chandigarh serving as his entry point into an increasingly competitive space. In any music industry, spotlight opportunities are limited, yet a decade into his career, Verma’s position remains unshaken. His knack for delivering successful collaborations and managing multiple projects simultaneously, while appealing to fans from Toronto to Sydney, has solidified his dominance on streaming charts worldwide.

It’s not just him either. Punjabi artists have been on a strong public uptick since the mid-2010s; a gradually rising tide that has seen representation across the globe. There’s AP Dhillon’s Juno Awards hype last year to Coachel la hosting Diljit, and even the likes of Drake mourning Sidhu Moose Wala’s tragic death in ’22 — a deeply personal wound for Verma, who referred to the former as a brother. Most of these men share the common journey of developing a love for music and creativity at a young age, before traveling abroad and working entry-level jobs to make ends meet, while writing and collaborating with others like them.

One struggle leads to another, it would seem. While some young artists land clean breaks early, Verma’s long stint in the Punjabi entertainment industry saw him work on endless scores of commercial projects — songs that stayed well within the comfort zone of himself and his associated labels but rarely pushed the envelope in terms of self-expression. It’s this that seems to hold back the industry today; cars, girls, wealth and power are all universally desired, and therefore hold universal appeal. But somewhere in between, the stories that actually made these artists who they are find themselves obscured. Verma was determined to step outside the shadow of labels and forge a more independent career to escape stagnancy — and the first step was to start producing more personal content through the people and places he called home.

Y Hate? — a recently released four-track debut EP — aims to open that door for Verma. Serving up references from Punjabi hip hop, folk and pop, Verma’s work on this EP dove deep into some of his personal adda cities — drawing on talent and on-site shoots across the streets of Sydney and Vancouver before bringing it back home to Patiala. He’s also doubled down on collabs — partnering with many of his previous collaborators such as Raftaar, Gurlez Akhtar and Laddi Chahal — putting together a drill-infused love letter to his friends, a ‘flex’ culture snapshot of his birthplace, and more. Apart from some of the year’s best Punjabi tracks so far, we’re witnessing what Verma alludes to as a second ‘coming of age’ — the renaissance of his relationship with his music, his personal world, and his outlook on life, success and fame, all of which we discussed during Verma’s brief visit to Mumbai.

Welcome to Mumbai! How does it feel to stop by here after quite a while?

Parmish Verma: The thing about Bombay is that I get to escape my everyday life. For me, Bombay feels like Australia… when I was there, I didn’t know anybody. It’s like being in a new playground, where you’re excited to see what next you can do. At the same time, you get to live it up here. When I was in Australia, I could have enjoyed my life in certain ways and I didn’t, because I was looking forward to my dream. I wanted to do certain things; it’s like going back in time now. Playing the same game, but as a mature person.

Speaking of traveling in time, let’s go back. You acted with your father not too long ago — how did your household influence you?

PV: I’ve always observed that people in interviews or TED Talks mention ki apne parents ke saath dialogue open kar lo. Like you noted, I had a great relationship with my father and was able to talk to him, when I was failing, not doing well, and felt that ultimately, hotel management, even if I scored the best results, was not a life that would make me happy. I told my father this at the age of eighteen, and he understood. I earned my own money since the day I landed in Australia, though I had some relatives there. I knew my financial limitations — how much money we had at home. When you know the economics of your household, it’s a great opportunity to be mature; if you’re irresponsible and don’t care, life won’t give you a bigger opportunity to be a man.

There’s an interesting common element here between you and other Punjabi musicians with similar journeys.

PV: See, creative fields require finances. We also grew up in households where we were ‘boys’ — there was a certain responsibility on [our shoulders]. We were the older kids of the house. You’re not sat down and told, ‘this is what you’re supposed to do’. You just know. Our parents could not afford to send us on a creative journey for ten years, wondering ‘what will happen if he doesn’t make it?’ Still, we knew our dreams, and we worked really hard, saved money, made sure our residency was secured… that’s when you transition. That’s when you give your dreams some time ki chalo, dekhte hain if I can live for myself. I think that mindset is embedded in all Indians, not just Punjabis.

How does a fan’s thought process work according to you, as a musician and as someone behind the camera?

PV: As an artist, this is my understanding — at least since going independent. I can’t comment on my music before that; but there’s a part of any music industry that focuses on ‘flexing’. Be it cars, be it muscles, power, weapons or clothes. I’ll be very honest here, but I don’t try to make the song desirable — I just love singing about hustle, hard work… and then success. It’s always about working hard, then celebrating it. An infinite loop. All my content comes from two sides of myself; the side of me that’s about the initial years, my dreams, aspirations, my struggles. They all form the ‘clay’ with which I build my content today. I go back there. And what do I have today? I have my family, my friends, a bit of success. All our music can be summarised in that.

You’ve become something of a fitness influencer too. What’s your fitness journey been like?

PV: I was a chubby kid. I grew up insecure, didn’t have that much money. I always thought that if I was strong, I could fight better. I didn’t have an elder brother and used to get bullied in school. There was no one to go to. I also have ADHD, so there was always so much internal chaos. Even today, there’s so much going on in my life. If you pay attention to what most artists post online each week, you only get to see those three or four beautiful moments, which are likely fake. No one gets to see the shit an artist deals with, personally and commercially. It’s important to have an active lifestyle, just so that you’re better equipped to deal with life. Especially for men, in today’s age. Men aren’t ‘seen’ these days, I feel that the world is so unfair to them. To many, men’s mental health is a joke. Gym is the only place that keeps me sane. I let out all my frustration, then go back to life.

Your music has an impact on many young men. If you had a son, what advice would you give him?

PV: I’d say the same thing to my daughter Sada; know what you want. The world today is full of knowledge, and a 15-year-old has more access to information than a 45-year-old professor just two decades ago. The issue is that the world lacks practice; even if kids consume good content, they’re watching so much of it without implementing anything. If you follow just one good idea, it could change your life. So, know what you want; it makes it so much easier to get wherever you need to be. After [Sada] was born, my perception changed a lot. She has a lot to do with my transition as an artist, because I now want to do things that I could show her someday. A lot of people come to me and say that songs like Aam Jahe Munde motivated their sons to work hard. It’s beautiful, as an artist — I imagine that my daughter will grow up one day and go like, ‘oh shit, this is what my dad believes in!’

How do you balance family life between work and travel, though?

PV: With a lot of borderline depression *laughs*. You know, I’d be lying if I said I could balance it, that I’ve cracked the code. It’s forever a situation of push-and-pull. You’re a father and a son; just as a man, your biggest task is to keep your family together, to give your child and your parents time. There’s a part of you that loses that battle… it’s about sacrificing yourself. But I think my family is very supportive too. My parents, my wife — they make it easy for me. We work as a team.

Do you have any role models or icons of your own?

PV: I used to, you know. I used to look up to a lot of people and follow their journeys. I respected them, but I felt down the line, they didn’t respect what they had, or who they were. Everyone’s idol f**ks up eventually, right? My idols now are people who have made mistakes — you learn more from people’s mistakes than their victories.

Y Hate is your first attempt at transitioning from commercial to relatively independent music; how did that phase shift affect you?

PV: During the post-pandemic era, my music was very specific — people enjoyed it for sure, but I felt like I was making the same song over and over and over again. When I was 25, I was a single bachelor living in a three-bedroom apartment playing cricket inside my house. It was fun, but then suddenly you’re 29. You don’t think about the same stuff anymore, you don’t want to sing about the same stuff anymore. That’s when I made Aam Jahe Munde… and no record label wanted to touch it. All the momentum of the audience backs off, along with the companies. It literally felt like finding my first listener again — we went from 700,000 listeners to 7 million. I pushed and put in my own money — the first song that took off was Zindagi. Then came Rubcion Drill, No Reason, Punjada… I just started working on songs that I personally loved, and talked about things that I genuinely believed in. Suddenly, Aam Jahe Munde — which hadn’t done well — blew up. My audience had evolved alongside me and was now able to accept this version of myself.

Why did you name the EP Y Hate? Who’s doing the hating?

PV: Haha. Long story short, there’s a music video of mine called Yaar Mere, where we used an Audi RS3 with a license plate reading Y HATE? It’s a nice car, grey with white rims and everything — a car that draws heads. And you know, in Australia or even over here, such cars stand out. People call them ‘goon cars’, you know — they get hated on. I felt like that. I’m like that car who stands out. People don’t like what they don’t understand or possess, and that’s okay, but why hate? I’m not even saying don’t — but it’s a question for yourself.

What’s it been like to collaborate with Raftaar?

PV: I’m big on drill music. Rubicon Drill, No Reason, The Hanuman, Ni Kudiye Tu… they’re all drill tracks, and I know Raftaar would kill it on these kinds of songs. But the reason I like him is because I find his way of working and his self-expression to be very similar to mine, He does a lot of commercial work too, but there’s also a part of him that’s very true and authentic. Songs like Never Back Down… they’re though provoking. Woh sikhate hain mujhe. He’s able to connect to that side of himself, he respects people who work hard, and he’s himself a hard-working guy. I like his energy and ethics.

It seems like there’s two sides to you; one that’s worked hard away from home, and one that celebrates success closer to your roots. The EP seems to be a way of you joining those parts of yourself.

PV: Man, you put it into words. I was just tired of pretending. I had created an online avatar of myself and got tired of playing that guy. I asked myself — what do I really have? 24 hours, that’s it. I really wanted to go back in time, to those days when I was working hard and struggling. I felt that on all levels, I was somehow happier. If I look at it now, after doing this for ten years… why? For a few nice cars? I love them and they make me happy, but none of it is worth it if you lose your peace of mind. There are different, vulnerable sides of myself that I want to sing and share with people. They may not sound as good or make me money, but those songs will have value. They’ll connect with people.

What’s next on the horizon for you?

PV: We’ve already shot and recorded Rubicon Drill 2, which I’ve worked on with Bohemia paaji. It might not have the same hook line or composition, but it’s a spiritual successor. That’s up first. Next is an album I’m working on, which I’ve named Unspoken Words. I’ve tried to include all my vulnerabilities in it, all my grey areas, all the thoughts I’ve been processing. It’s very non-commercial and might not work or make money, but people would love the songs. If you’re having a rough day and you’re a genuinely self-made man or woman… if you’re on that journey, then these songs are for you.

Credits:

Editor: Shivangi Lolayekar (@shivangil23)

Photographer: Rohit Gupta (@rohitguptaphotography)

Stylist: Manpreet Kaur (@manpreetkaur15)

Art Director: Hemali Limbachiya (@hema_limbachiya)

Head of Production: Siddhi Chavan (@randomwonton)

Makeup: Hardeep Arora (@hardeeparora12)

Hair: Suraj (@sunshinehairndbeauty)

Music Partner: Believe Artist Services (@believeasd)

From Man’s World India.